The 25 Best Live Rock Recordings - Coda

A Prelude To The Coda OR The Random Thoughts of a Music Obsessive

There is a bit of housekeeping before revealing the No. 1 Best Live Rock Recording. It involves three words in the series title: Live, Rock, and Best. To clear my mind, I want to address what is special about live recordings (as well as some significant pitfalls). After that, I want to look at the skeleton of rock music and consider its cultural importance. And last, I want to apologize for even suggesting such a list…what qualifies me to say, and who do I think I am, anyway?

And…I want to get even with the Philistines claiming history as their own…

Live Recordings

Our exposure to popular culture shapes us. Our aesthetic sense develops as we identify the elements of popular culture and put them into a personal context. For me, that context was music. And that music was rock & roll.

It was somewhere between first hearing Three Dog Night’s Captured Live At The Forum (ABC/Dunhill, 1969) and Little Feat’s Waiting For Columbus (Warner Bros, 1978) when I realized that live recordings hold a special significance. Or not. Commercially released live recordings had a reputation for being instruments of contract completion: often poorly produced throw-offs where the artists no longer cared and neither did the sponsoring record companies.

The Eagles Live (Asylum, 1980) was an example of such an unfortunate release. The band released the recording at the end of an acrimonious breakup to fulfill their contract with Asylum Records. Guitarist Glenn Frey and drummer Don Henley decided to complete this obligation with a live recording documenting the Hotel California (Asylum, 1976) and The Long Run (Asylum, 1979) tours. With Frey in Los Angeles and Henley in Miami, the two communicated and completed the project called “the most over-dubbed concert recording ever” via air mail (email was not a thing at the time) rarely, if ever, talking.

Elektra/Asylum offered Frey and Henley $2 million to write two new songs to add to the live set to help encourage sales. That did not happen, but the two did squeeze out a previously recorded a cappella version of Steve Young’s “Seven Bridges Road” that the band used to tune their harmonies before performing. With that, the Eagles released an afterthought that peaked at No. 21 on the Billboard Top 100 proving absolutely nothing aside from an adoring public ignoring the disappointment that was The Long Run because they remained too high from the “…warm smell of colitas rising up through the air.” The result was a patchwork of performances, inspiring as beer bottle backwash, that were simply studio regurgitations with nothing new to say.

And that is too bad. Live recordings should reflect how a band sounds performing live, not in the studio. They should allow bands to stretch out and do something different with improvisation, seasoning their playing with piquant surprises. Clever song segues can often delight like Thin Lizzy’s coupling of “The Cowboy Song” with “The Boys Are Back In Town” on Live And Dangerous (Warner Bros, 1978) or the Bob Seger diptych “Travelin’ Man” and “Beautiful Loser” on Live Bullet (Capitol, 1976), or even Lowell George’s positioning of “Time Loves A Hero” to dissolve into “Day Or Night” from Waiting For Columbus (Warner Bros, 1978).

Jam bands like the Grateful Dead, Phish, and later, Goose and Dogs In A Pile have made a cottage industry of recording a studio album and then using that material for lengthy expositions of virtuosity (or boredom, depending on how one hears it) live in concert. These bands introduced the paradigm of recording every show, releasing each two or three days later on a platform like Bandcamp. Each band has formed a loyal following with this business method. But this is not a new pattern, as jazz musicians have been doing something comparable since Louis Armstrong tooted the opening notes to “West End Blues” (Okeh) in 1928.

However, there is a bit of deceit involved in releasing live recordings. Very rarely does a live recording make it to disc unedited or un-remixed. One such live recording that avoided intense prerelease editing was Grand Funk Railroad’s Live Album (Capitol, 1970). Also, live recordings rarely portray the accurate order in which songs were played. One that did accurately reflect the performance order was the Allman Brothers Band At Fillmore East (Capricorn, 1971), but the recording underwent some other studio magic per producer, Tom Dowd.

Another deceit is that producers and bands often return to the studio to re-record vocal or guitar parts, one of the most famous having made this list at No. 2, Little Feat’s Waiting For Columbus. Lowell George produced the recording and took advantage of his studio savvy to doctor the tapes, improving his vocals and slide guitar playing. YouTube videos of the shows recorded on the album reveal George’s often careless lyric treatments, as well as his stinging slide guitar solos, which occasionally left the tracks altogether. I will continue to defend this collection as a fine live recording, with warts and all being revealed on subsequent release of the material.

Studio cleansing aside, the best live recordings that make up this list provide an organic listening experience where the seams in the music so carefully disguised in the studio become apparent, allowing the listener a look under the hood of song arrangement and execution. Fans should consider it a welcome, rather than unfortunate, occurrence for a reputed "studio" band to get on stage and spring a couple of leaks that add to the excitement of the live performance, which is already a high-wire act. For example, look no further than Led Zeppelin. Listen to the 7:00 of “No Quarter” from the studio recording Houses Of The Holy (Swan Song, 1973) and compare that with the 20:17 of the same song from Four Blocks In The Snow (The Chronicles Of Led Zeppelin, 2008) and get a snootful of what is great about live recordings (particularly unmolested soundboard recordings).

Before sound recording, live was the only way to experience music. While not perfect, live recordings remain a means of vicariously enjoying a concert. As documentation, they are often the only tether to what performers “really” sound like.

Rock & Roll

The ontology of music has evolved to the point of meaningless atomization. Recently researching “ambient music” revealed a subordinate subcategorization: Ambient dub, ambient house, ambient techno, ambient industrial, ambient pop, dark ambient, and space music. Exploring Ambient pop reveals connections to other styles like post-rock, dream pop, and shoegaze. Within shoegaze, there are subgenres like Chillwave, nu-gaze, and Blackgaze, leading to a continuous breakdown until there is nothing left.

Rock music (even without the phrase "and Roll" delineated from the original) has experienced the same fate, necessitating some grounding definitions. By utilizing the egalitarian resource, Wikipedia, people define rock & roll music as:

“…a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm and blues, boogie-woogie, electric blues, gospel, jump blues, as well as country music. While rock and roll's formative elements can be heard in blues records from the 1920s and in country records of the 1930s, the genre did not acquire its name until 1954.”1

(Note the atomization of the blues) What was so great about 1954? Cleveland radio personality Alan Freed changed the name of his syndicated radio show from “Moondog House Party” to “The Rock & Roll Show.”2

A Brief Interlude (or “I am going to lose my mind one more time over something socially meaningless”)

This is why Cleveland ostensibly received the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame over Memphis. This and Cleveland were Presley’s first concert outside the traditional South (or, more appropriately, inside the traditional North, at the Circle Theatre, Cleveland, OH, October 19, 19553).

How lame is that?

Memphis, the ground zero for making rock & roll, is famous for losing sports franchises and other attractions that it was otherwise entitled to have. When the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame went to Cleveland for the rationale above, Ahmet Ertegun, chairperson of the Hall of Fame Foundation, further reasoned, “We’re not going to make this a rock ‘n’ roll Disneyland. We have an obligation to the world of rock ‘n’ roll, the artists and the fans, to make this a dignified place they can be proud of.”4

What an amazingly large and aromatic crock that is considering the Hall’s promiscuity for inducting anything but rock & roll since its inception.

From the same LA Times article providing Ertegun’s reasoning, a short and tidy question emerged in the face of overwhelming criticism.

“So where does history tell us the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame belongs?

The answer: Memphis. No place else is even close if the decision is based on which cities most nurtured this maverick music—the cities where rock was born in the ‘50s and where it matured in the ‘60s.

1—Memphis. Even without going back to the city’s roots in the blues and the contributions of such seminal figures as Howlin’ Wolf, this city would finish on top if we merely began our evidence with Elvis Presley’s first recordings in 1954 at Sam Phillips’ Sun Records studio--the music captured in the RCA album, “Sun Sessions.”

In those historic, pre- “Heartbreak Hotel” recordings, Presley and Phillips brought together blues and country influences in a way truly defining rock ‘n’ roll. Besides his work with Presley, Phillips (who was one of five “pioneers” also inducted into the Hall of Fame in January) helped popularize the rockabilly genre, working with Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Charlie Rich and Carl Perkins. The Burnette Trio also contributed to the Memphis rockabilly movement.

Where this country side of Memphis rock dominated in the ‘50s, the city became a stronghold in the ‘60s for soul music, serving as the recording base for Otis Redding, Booker T. and the MGs, Wilson Pickett, Isaac Hayes, Sam and Dave, the Staple Singers, Johnny Taylor, Willie Mitchell, and Rufus and Carla Thomas.

Locating the Hall of Fame in Memphis also [would have made] sense for cultural and geographical reasons (indicative of the Southern influence on rock, all 10 of the initial inductees were born in the South). Where Los Angeles and, especially, New York served as symbols in the ‘50s of the record-biz Establishment that renegade rock musicians had to battle, Memphis had a reputation as an underdog and tough—like rock itself.

In visiting Memphis, tourists would also be able to visit Elvis’ home (Graceland) and birthplace (Tupelo, Miss.). Ironically, the latter facts are considered strikes against the city. “Memphis is connected in the minds of the public with Elvis Presley and Graceland,” said one foundation representative, “and we wanted a city where we could establish our own identity. We wanted a city that had no strong identity with any one person or type of music, i.e., New Orleans and jazz, Nashville and country music.”

Said a “foundation representative.” That is one rare vintage of sparkling fuckery, if you ask me.

The other suggested sites were Los Angeles, New York, New Orleans, Chicago, and Detroit. This should not have been a choice but a foregone conclusion. Such was this squandered opportunity.

That being said—

When did rock music start and when did it end? NPR’s "rock & roll historian" the late Ed Ward started his The History of Rock & Roll, Volume 1: 1920-1963 (Flatiron Books, 2016) by discussing Mamie Smith’s 1920 recording “Crazy Blues” ((Okeh Records (4169-A), 4169-B “It's Right Here For You (If You Don't Get It-'Taint No Fault O' Mine)”) and ended his The History of Rock & Roll, Volume 2: 1964–1977 (Flatiron Books, 2019), the only way he could, on August 16, 1977.

I am going to approach this differently by suggesting several milestones be considered (this is highly opinionated and should the reader not agree they may side with any of the gazillion opinions in print):

The first rock & roll record was “Rocket ‘88’" by Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats recorded at the Memphis Recording Service (which shared a building with Sam Philips’ Sun Records) and released on Chess Records, on March 3 or 5, 1951. Philips was the producer of record. “Rocket ‘88’" has a twelve-bar blues structure and was credited to Jackie Brenston. Brenston was Ike Turner's saxophonist and the Delta Cats were, in reality, Turner's Kings of Rhythm, who rehearsed at the Riverside Hotel in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

Brenston sang the lead vocal on the song and is officially listed as the songwriter. Turner led the band and was more than likely the actual composer.5 So was “Rocket ‘88’” the first rock & roll record? Ike Turner revealed in an interview with Canadian radio broadcaster Holger Petersen,

“I don't think that "Rocket 88" is rock 'n' roll. I think that "Rocket 88" is R&B, but I think "Rocket 88" is the cause of rock and roll existing ... Sam Phillips got Dewey Phillips to play "Rocket 88" on his program–-and this is like the first black record to be played on a white radio station—and, man, all the white kids broke out to the record shops to buy it. So that's when Sam Phillips got the idea, "Well, man, if I get me a white boy to sound like a black boy, then I got me a gold mine," which is the truth. So, that's when he got Elvis and he got Jerry Lee Lewis and a bunch of other guys and so they named it rock and roll rather than R&B and so this is the reason I think rock and roll exists—not that "Rocket 88" was the first one, but that was what caused the first one.”

That is good enough for me.

The last rock & roll record was Appetite For Destruction (Geffen, 1987) by Guns N’ Roses. The event that ended rock music as “popular music” has been a topic of discussion for quite some time. Rock music’s decline began as a function of rap music’s ascension in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, supporting my supposition. Complex metrics aside, if we compare units sold, as of 2023, Appetite for Destruction had sold more than 30 million copies. No similar act has eclipsed this after them. Not Nevermind (26 million), not Joshua Tree (25 million), and no one else was even close.

GNR was the last band from the blues-based rock arc that included the Rolling Stones, Faces, Humble Pie, Aerosmith, and the thousand bastard children of Led Zeppelin.

A brief interlude on the morality of rock & roll music:

Were any of these bands role models for America’s (or anyone’s) youth?

No.

They represented what rock music was all about — a swaggering attitude of youthful angst, discontent, disappointment, limitless creativity, and excess. Robbie Robertson, founding member of The Band, once said “Music Should Never Be Harmless.” Extrapolating that thought music should never be safe, either. It should be subversive and culturally upending. It is an art about tearing down to build something new and better, and, if not better, uniquely different. It should be summed up in Rolling Stone’s “Gimme Shelter” or GNR’s “Welcome To The Jungle” and not the Beatles’ “Michelle” or “I’d Like To Buy The World A Coke.”6 No, rock & roll music was about sticking one’s finger into the eye, up to the second knuckle, of America’s postwar complacency.

Rock music was never about comfort or the Roman Catholic ideal of “suffering in silence.” Rock music is about spraying that corrosive Alien slime everywhere, singing not just any ideal, but all ideals…always asking “Why?” on one end or “What Difference Does It Make?” on the other. Rock music was never nihilistic unless that nihilism was part of a transformation—metamorphic and evolutionary.

The rock-as-the-popular-music era began—on July 19, 1955, with the release of Elvis Presley’s cover of the Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup composition, “That’s All Right” (Sun Records). The era had to start somewhere, and this was a pretty obvious place.

The rock-as-the-popular-music era ended—on September 11, 1990, with the release of Warrant’s Cherry Pie (Columbia). I had read (or heard) this suggested several years ago and can no longer find a legitimate source. So, without a shred of evidence, I will double down on this: “Cherry Pie” killed rock music just as surely as did Styx’s “Mr. Roboto” from the equally depraved recording Kilroy Was Here (A&M, 1983).

The Day The Music Died—on October 28, 2022.7

Who Appointed Me Music Know-It-All?

My nephew asked me (before he knew better), “What qualifies you as an expert to write about anything, much less music?” A great, but misguided, question. I have never claimed to be an expert on anything. I have never claimed nor do I have the academic credentials to be considered a professional journalist. Some tell me I am a professional because I have written about music for 30 years. I remain unconvinced.

I prefer to think of myself as a “music enthusiast” whose introduction to music early led to an omnivorous consumption and consideration of the art, at best, or an officially elderly (defined as people 65-years old and older) individual with the mind and taste of a 13-year-old boy who never outgrew his pathologically obsessive love for music, at worst.

I have looked for some justification for making a list like the “25 Best Live Rock Recordings” and the only thing I can come up with is … “for the love of it.”8 I did not understand this list until I read a similar one about baseball players written by Joe Posnanski, The Baseball 100 (Simon & Schuster, 2023) and Why We Love Baseball: A History in 50 Moments (Dutton, 2023), Posnanski cleverly narrates a history of baseball every bit as riveting as Ken Burn’s 1994 documentary.9

When Posnanski finally got to No. 1, the surprise was already realized with Babe Ruth at No. 2. After a Moby-Dick number of words; the author arrived at the only player that made sense, Willie Mays. In a book as densely based on statistics and sabermetrics, Posnanski distilled his reasoning down to childhood and memory, statistics, and legend. In Posnanski’s words:

“Can anyone know [who the greatest baseball player is]?

But wait! Of course we can know. More than that: We do know. We know the answers to all these questions and more because … well, because we know. See, all along, this journey has not just been about the greatest players in baseball history. It has been about us, too: fans. It’s about the things we believe in, the myths we hold dear, the statistics we embrace, the memories we carry.

…

Who is the greatest player of all time? You know. Maybe your father told you. Maybe you read about him when you were young. Maybe you sat in the stands and saw him play. Maybe you bask in his statistics. The greatest baseball player is the one who lifts you higher and makes you feel exactly like you did when you fell in love with this crazy game in the first place.”

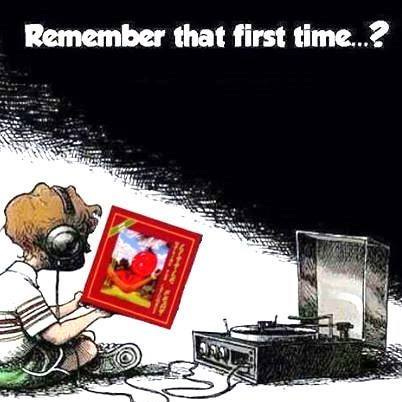

It is the same with music and unimportant lists like this one. It is a growth experience where one grows to a threshold where all becomes clear and one’s vision and understanding zoom out to the full 360 degrees. It comes back to, “Do you remember that first time…”

Wikipedia Contributors. “Rock and Roll.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, December 28, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_and_roll.

Dawson, J. and Steve Propes. What Was the First Rock 'N' Roll Record? New York: Faber & Faber, 1992.

Concertarchives.org. “Elvis Presley,” 2022. https://www.concertarchives.org/bands/elvis-presley?page=46#concert-table.

Hilburn, Robert. “Misplacing Rock’s Hall of Fame?” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1986. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-03-02-ca-1291-story.html#:~:text=He%20suggested%20that%20a%20major,the%20Hall%20of%20Fame%20foundation.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Rocket 88.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, November 26, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocket_88.

Wald, Elijah. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bailey, C. Michael. “Jerry Lee Lewis: 1935 - 2022.” All About Jazz. Allaboutjazz.com, November 3, 2022. https://www.allaboutjazz.com/jerry-lee-lewis-1935-2022-jerry-lee-lewis.

C. Michael Bailey. 2024. “For the Love of It All.” Wildmercuryrhythm.com. Wild Mercury Rhythm. January 31, 2024. https://www.wildmercuryrhythm.com/p/for-the-love-of-it-all.

Burns, Ken, and Lynn Novick. Baseball, National Endowment For The Arts, 1994.