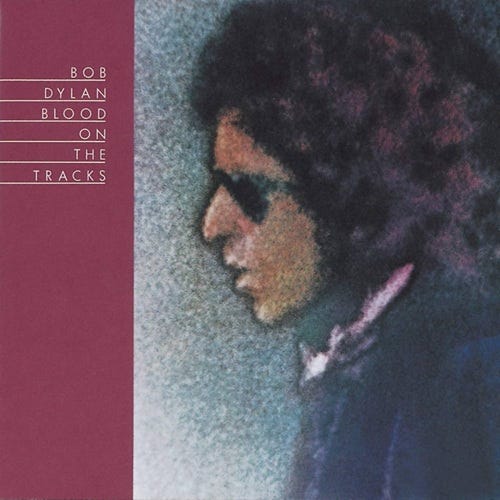

Blood on the Tracks at 50

When life got really messy, Bob Dylan turned pro...

“Bob is Bob1. Even Bob doesn’t know that Bob was doing…”

—Sturgis Nikedes

I was a little too young to have experienced Woodstock firsthand. I watched the movie (Warner Bros, 1970) in 1972, purchased Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More (Cotillion, 1970) and Woodstock Two (Cotillion, 1971) in 1974. It was during this period that I assimilated my early tastes of the music of the era shortly before my awareness of it manifested…along with the rise of The Allman Brothers Band, The Marshall Tucker Band, ZZ Top, and Lynyrd Skynyrd, and the rest of what was called “Southern Rock.” My musical palate would become more complete with my sporadic realization of where blues-based rock came from. First, it was Joe Cocker with that perfectly imperfect voice, ending with my growing appreciation of Led Zeppelin as the band taking the electric blues as far as they could.

In 1974, I had my late introduction to Bob Dylan and The Band. It would be 40 years later that I would confront the enormity of the two. My introduction was the double LP live recording Before the Flood (Asylum Records, 1974). While I circled back and picked up The Band’s Rock of Ages (Capitol Records, 1972), fully embracing Jamie Robertson’s Norman Rockwell’s bad-on-the-moonshine dark agrarian vision of America, I never did the same with Bob. That lay in the future. Instead, it was Bob’s fearless recasting of his most notable songs on the album rather than the originals that alerted me to what I was missing. I did not know of the connection between The Band and Bob. I would soon learn, but still concentrated on The Band.

On January 20, 1975, Columbia Records released Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. Now, this album got my attention. I had just been too young for the thrill of hearing the introspective becoming extroverted on Highway 61 Revisited (Columbia Records, 1965) and Blonde On Blonde (Columbia Records, 1966) right out of the shrink wrap. Instead, what I first experienced of Bob after BTF was the universe of Dylan’s anger and rage expressed on Blood On The Tracks. Where Jackson Browne’s Late For The Sky (Asylum, 1974) touched what sadness I had in my brief life, BOTT showed me the intense angst and ecstasy of love, its opposite, and everything in between and how quickly one could become the other.

The origins of the material are murky, but owed to the devolution of Dylan’s relationship with his wife, Sara Lownds. After concluding the 1974 tour that resulted in Before The Flood, Bob began a relationship with Ellen Bernstein, an employee of Columbia Records. In the summer of 1974, Dylan wrote a series of songs that he would take, along with Bernstein, out to his farm in Minnesota, where he completed the songs that would become the album. This is Bob at his most expansive (“Tangled Up In Blue,” “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts”), his most vulnerable (“A Simple Twist of Fate” “Shelter From The Storm), and his most angry (the brilliant “Idiot Wind”).

The songs have passed into Myth, joining the thrashing arrogance of Icarus flying too close to the sun and the grinding frustration of Sisyphus pushing his rock. Bob clearly experienced his emotional release at both ends. Delicious was the first, second, and one-millionth listening to “Idiot Wind.” The opening stanza was Bob at his angriest and paranoid, ending with his greatest kiss-off:

Someone's got it in for me

They're planting stories in the press

Whoever it is I wish they'd cut it out quick

But when they will I can only guess

They say I shot a man named Gray

And took his wife to Italy

She inherited a million bucks

And when she died it came to me

I can't help it if I'm lucky

Forget what Mr. Jones knew and how Hattie Carroll died. Bob has moved on, and Mr. Jones lay in the ditch, with Hattie Carroll assumed whole into what passes for heaven, just like the Blessed Virgin. Bob is well past “Maggie’s Farm” and “Masters of War.” Like Byron on an opium jag, the words and images pour out like so much tainted kerosene, a schizophrenic word-salad giving birth to the bright light of:

There's a lone soldier on the cross

Smoke pourin' out of a boxcar door

You didn't know it, you didn't think it could be done

In the final end he won the wars

After losin' every battle

Whatever he meant, grafting World War I and the Dust Bowl together with the conversion of St. Paul.

But no one can sustain such Sturm und Drang, not even Bob. He eventually has to swing back to the middle, to a place of safety where he can reflect:

I've been meek

And hard like an oak

I've seen pretty people disappear like smoke

Friends will arrive, friends will disappear

If you want me

Honey baby, I'll be here

And, indeed, he has.

Thinking of my life's mentors, Garry and Jane Reifers and Alex Lankford, interpreters for Bob when he speaks in tongues.

Exodus 3:14.

Exceptional.