The 25 Best Live Rock Recordings - An Afterword

When a single performance sums up an entire epoch.

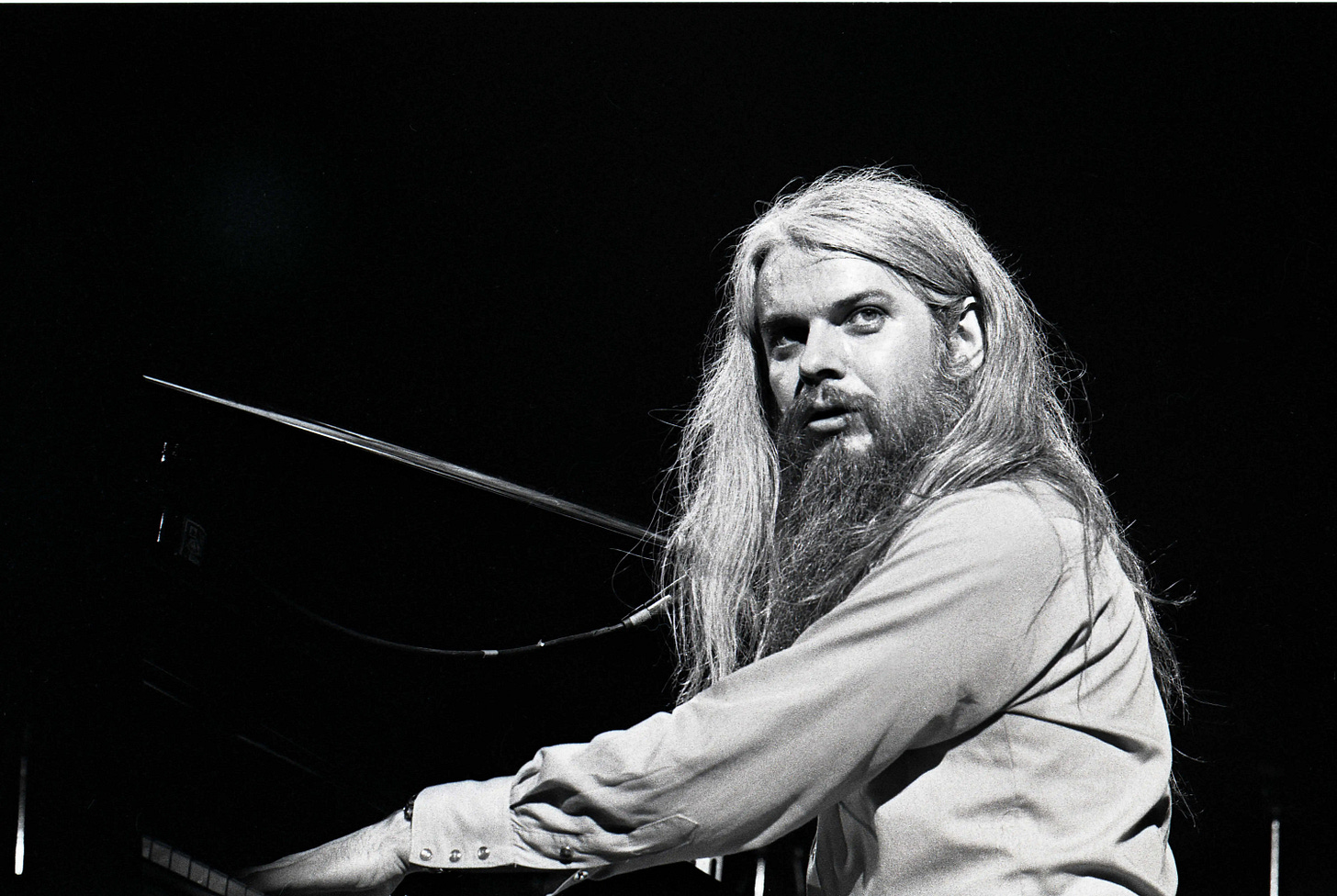

“Somebody you all know by now—Leon…”

This is how George Harrison introduced the outlier of the Concert For Bangladesh. Russell seated himself at the piano, and fellow Tulsa native Carl Radle (Russell was from Lawton, but close enough for us here) took over the bass chair from Klaus Voorman. Don Preston, who, with Radle, were part of Russell’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen band, exited the choir, strapping on his Gibson Explorer and joining a guitar line that included Jesse Ed Davis, George Harrison, and a badly dope-sick Eric Clapton playing an ill-suited Gibson Byrdland). The first notes Russell played were a seismic eruption, no, a detonation, of 10 minutes of evangelical (before that was a bad word) thunder and lightning, changing the benefit concert's somber trajectory toward a Hell-hot Summer Oklahoma tent revival.

By the time Leon Russell sat down at the piano and burned down Madison Square Garden on August 1, 1971, he had already been a part of the Los Angeles studio scene since the early ‘60s as a part of the “Wrecking Crew.” His services appeared in albums by Frank Sinatra; Aretha Franklin; Jan & Dean; the Ventures; the Everly Brothers; Billy Strange; Gary Lewis and the Playboys; the Beach Boys; the Byrds; Glen Campbell (also part of the Wrecking Crew); Del Shannon; Bobby Vee; Delaney & Bonnie; Joe Cocker; the Rolling Stones; Eric Clapton; Dave Mason; the Flying Burrito Bros.; B.B. King; the Carpenters…are you getting the idea?

Most of these recordings buried Russell in the recording credits. It was not until early 1970 when Denny Cordell asked Russell to help man the helm of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour he became a full-fledged superstar. Many critics believe he did so at the expense of the headliner. To be sure, Russell was extroverted on stage and off, a take-charge music director with a knack for the large logistics of a concert tour. The introverted Cocker, with his backside in a crack at the time of the tour (circumstances described elsewhere), lacked the bandwidth to pull such a thing off. Russell pulled together a crack band and gave the show its cultural center and flavor outside Cocker’s one-of-a-kind voice and interpretive ability.

Three days after commencing Mad Dogs and Englishmen, Russell released his solo project, Leon Russell, on his Shelter Records label. That recording included “Delta Lady,” “Dixie Lullaby,” and “Hummingbird.” with the former being performed definitively by Cocker during Mad Dogs and the latter two by Russell, during his segment of the concert. Russell’s investment in the tour was large and would ignite his public career as much as it did Cocker’s. Mad Dogs was never just about Cocker alone, it was about Cocker and Russell. Had either principal been missing, there would have been no Mad Dogs.

After Mad Dogs, Russell worked on his follow-up to his debut recording between August 1970 and January 1971, releasing his breakthrough Leon Russell And The Shelter People (Shelter) on May 3, 1971. Included were the Russell staples “Stranger In A Strange Land,” “Of Thee I Sing,” and “Crystal Closet Queen.” Russell covered Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry” and George Harrison’s “Beware Of Darkness” from that former Beatle’s recently released All Things Must Pass (Apple, 1970). Russell refined his band format, taking what he developed during Mad Dogs, and keeping the “choir” setup for support vocalists, twin drummers, and keys. Russell instilled the spirit of a midsummer tent meeting into every song.

While touring to support Leon Russell And The Shelter People, Russell received a telephone call from George Harrison, asking him if he would play in a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden on August 1. The concert and Harrison’s part in it came about when Harrison’s good friend Ravi Shankar asked him to help the people of his home, Bangladesh, who were experiencing a humanitarian catastrophe. The Concert For Bangladesh was the first superstar benefit concert. Over the next three weeks, Harrison got commitments from Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Jim Keltner, Klaus Voorman, Badfinger, and Russell, with Bob Dylan breaking at 50:50 that he would show up at all.

But Dylan gave in and agreed to take part, and Russell and Harrison sorted out the performance logistics.

The performances started with an exposition of Indian music led by Shankar, setting a liturgical and solemn tone. Next, producer Phil Spector led the band onto the stage, where, once assembled, it launched into Harrison’s musical middle finger to former bandmate, Paul McCartney, “Wah Wah” from All Things Must Pass. Subdued even in the upbeat songs, Harrison is simmering and the show warming. After “My Sweet Lord” and “Awaiting On You All,” Billy Preston presented his “That’s The Way God Planned It” (Apple, 1969) followed by Ringo Star playing his latest single, “It Don’t Come Easy” (Apple, 1971). Both songs were radio fodder, softballs thrown to an appreciative audience. But then a change in ambiance occurs; things warmed with Harrison’s “Beware Of Darkness." Harrison sang the first two verses with Russell picking up the third, having covered the song on Leon Russell And The Shelter People. The effect was electric, and the crowd responded with added zeal.

Leon Russell had arrived and this would be his zenith.

The next song played was Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps." An anchor for the Beatles’ The Beatles, aka, The White Album (Apple, 1968). On the original, Clapton provides a history-making solo using Harrison’s Gibson Les Paul. Now Clapton, while experiencing opiate abstinence syndrome and deeply sullen, played an ill-suited guitar for only God knows why, performing as badly as he felt. While warmly received, the performance is a low point in the concert.

Leon is next. He takes a seat at the piano and the gestalt of the moment is best described by his biographer, Bill Janovitz in Leon Russell: The Master Of Space And Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History (Hachette, 2023):

“Fresh from the sting of the accusations of spotlight-stealing on the Mad Dogs tour, Leon displays unshrinking audacity to frame a ten-minute medley within a Stones song in the middle of a charity show by half of the Beatles in front of a sold-out Madison Square Garden. And though the focus of the event was to benefit a nation in the throes of a humanitarian catastrophe, Leon felt no compunction to keep the show solemn; it was a rock ‘n’ roll audience, who had waited in line, some overnight. The best way to respond to a grim situation is with fervor, love, empowerment, righteous anger, and shining blinding light in the face of the daunting darkness.”

With three staccato B-flats, Leon Russell sharply changes the momentum and direction of the concert from one of resigned hope to one of bold and assertive action. Singing with his voice full of dust-bowl grit, Russell summons no less than the spirit of the Divine to come and cleanse and redeem by fire. “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” is an anthem to persistence and rage and never quite finding a resolution. It is all pent-up pathos—approach, and release when Russell slides into the DM of the Stones’ song with a throwback, The Coaster’s 1957 hit, “Youngblood” (ATCO) turning the heat and humidity up with his sexy sermon on love and temptation. Don Preston sings the bridge and the song returns to an ebbing gospel tide of build-up and release until finally, Leon relays the words of his lover, singing softly in his ear… “Well, it’s alright now, in fact, it’s a gas…”

The song ends in a grand Leon Russell-style, becoming the most memorable performance on the LP release. That day, Russell had all the virile charisma and country mojo, his and everybody else’s. He railed like a sweating, jake-legged Pentecostal preacher on a summer Sunday night, closing the tent. This is the most important performance of the concert and Russell presented it. Robbie Robertson said that music “should never be harmless” and Leon Russell took him at his word.

PostScript:

Leon Russell was born Claude Russell Bridges; April 2, 1942, in Lawton, Oklahoma. Many might not consider Oklahoma a musical mecca at first thought until we consider that The Sooner State was home to, besides Russell, the “First Lady of Rockabilly” Wanda Jackson, Woody Guthrie, J. D. McPherson; rock & roll artists J.J. Cale, Carl Radle, The Flaming Lips, Cody Canada & Cross Canadian Ragweed, Dwight Twilley; jazz artists Don Cherry, Chet Baker, Sunny Murray, Charles Brackeen, Sam Rivers, Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey, and Charlie Christian. A score of country music artists hail from Oklahoma; that goes without saying or mentioning.

But none of these artists had the cultural reach of Leon Russell, one of the most distinctive singers, pianists, producers, and bandleaders in rock music. His unique singing style derived from his twangy Oklahoma roots, dry as dust in a whirlwind. His unique piano style (as well as the noticeable limp he carried throughout his life) was due to what is now called cerebral palsy. Russell sported a weakness on his right side that gave his left side the bulk of his power. It is what gave him his powerful left hand at the piano (think of his playing on Joe Cocker’s “The Letter” and “Space Captain” from Mad Dogs & Englishmen or “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” mentioned above). What is certain, one knew it was a Leon Russell arpeggio when one heard it, as well as his lightning fast octaves, thrown off as if shaking the sweat from his face.

Russell died on November 16, 2016. I pride myself on writing obituaries for the artists most important to me, but I missed the biggest and bassest of them all. So, this brief missive must suffice. Russell deserves much more, but how can anyone do justice for such talent?

Elton John, Russell's protégé from the early 1970s, brought him back into the spotlight one last time at the end of his life, resulting in his induction into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame (one of the few sensible decisions made by the Hall’s administration). The two recorded The Union (Decca, 2010) and their efforts earned them a Grammy Award nomination. Before John became his advocate so late in life, Russell feared falling into obscurity or worse, irrelevance.

But the “Master of Space and Time” did not go so gently, as we could only expect. He framed himself best in one of his songs, one with the potent scriptural overtones so prominent and close in his music:

“Roll away the stone

Don't leave me here all alone

Resurrect me and protect me

Don't leave me layin' here

What will they do in two thousand years…”

Thinking of Garry Reifers and Cindy Sims Lasseter, fellow lovers of Leon, friends old and new from Okalona, Mississippi.