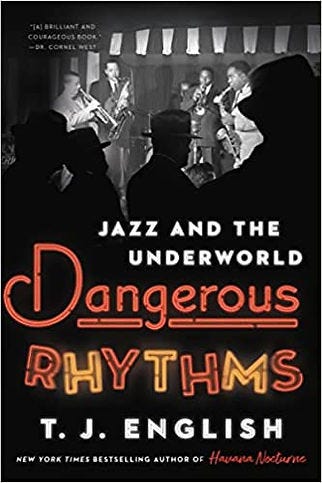

Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz And The Underworld

T. J. English, (William Morrow & Co, 2022)

T. J. English has made a cottage industry of writing about organized crime, beginning with his widely admired The Westies: Inside the Hell's Kitchen Irish Mob (G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1990), which he followed with Born to Kill: The Rise and Fall of America's Bloodiest Asian Gang (William Morrow & Co, 1995), Paddy Whacked: The Untold Story of the Irish American Gangster (HarperCollins, 2005), and Havana Nocturne: How the Mob Owned Cuba and Then Lost It to the Revolution (William Morrow & Co, 2008). So, what makes English so unique? He is not writing in a vacuum with dozens of other authors commenting on the history of the Mafia in America. What sets English apart is his keen narrative ability. His books are well-researched but they smack not at all of dry history or pedantic pathos. English tells a story, giving immediacy to his topics and a street-level view of his subject.

English is also an experienced enough writer to know when tangent projects present themselves, like jazz and its relationship with organized crime in his recently published Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz And The Underworld. The two subjects intersect conveniently, each appearing in the evolution of the other. English begins in New Orleans in the Storyville Red-light District and Joe "King" Oliver and Louis Armstrong, heading upriver to St. Louis and over to Kansas City, an open territory if there ever was one, where the author spends much time on the Pendergast Brothers and the parts they played in supporting venues for the territory bands of the 1920s and '30s.

Kansas City provided an incubator for artists such as Bennie Moten, William "Count" Basie, and Oran "Hot Lips" Page. Contemporary with KC was Chicago and the Mob's presence during Prohibition, replete with Al Capone and other assorted thugs, again with "King" Oliver and Louis Armstrong, who followed work to the Windy City. New York City and Los Angeles loom large in English's account with much attention paid to Morris Levy and Frank Sinatra and their roles in music and organized crime. Sinatra does not come off much better than Levy, and that is saying something.

Perfectly clear from the book was the low commodity status of black musicians, who were viewed and treated like second-class musicians as well as citizens. While the symbiosis was strong between jazz and organized crime, black musicians were still treated with the not-so-casual racism of the Jim Crow era. Marginalized and threatened, the black jazz musician was considered expendable if not maintaining a cash flow. Brutal and often depraved, English's superb narrative account pulls back the curtain on what was always assumed...that crime was conducted better with a live soundtrack. And, what a live soundtrack it was.