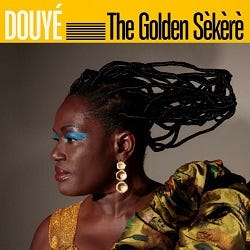

Los Angeles vocalist Douyé releases her fifth recording with The Golden Sèkèrè, her second collection of jazz standards after her well-received 2017 release Daddy Said So (Rhombus Records, 2017). Douyé also released a terrifically straight-ahead disc in Bossa Nova Deluxe (Rhombus Records, 2019). Returning to jazz standards, The Golden Sèkèrè is not merely a continuation of the high-functioning Daddy Said So. It is the first significant change in the stylistic approach to jazz standards in 30 years.

The “Great American Songbook” is a loose assembly of American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century. The Songbook includes Tin Pan Alley standards and songs composed for musical theatre and film from the 1920s to the 1950s. This body of music has demonstrated a fertile resilience, having been performed and reimagined countless times in many ways over the last century. With many recordings devoted to this repertoire available, projects addressing the canon today demand an added level of invention and innovation to continue to be relevant.

Cassandra Wilson was the last singer to creatively impact the Songbook with her string of ‘90s Blue Note Record releases using rustic instrumentation and inspired arrangements. Douyé is doing the same thing by tapping into her Lagos Nigerian roots to extract authentic African beats and rhythms with which to season her new collection, The Golden Sèkèrè. The title refers to an African percussion instrument consisting of a gourd surrounded by a net of beads that can be shaken, slapped, or twisted to produce a subtle variety of sonic and rhythmic sounds. African percussionist Najite Agindotan plays a central role in this new recording.

Douyé achieves this new Songbook interpretation through arrangement and the judicious use of like-minded West African musicians producing singular African rhythms. This cultural coloring differs from Cubano and Caribbean influences in having a decided lack of sonic humidity. The African rhythms and elements the singer uses imbue the music with a warm and dry character, like robusta roasted coffee on a warm morning compared to the Caribbean condensation on an afternoon Daquri.

The African influence is one of three innovations Douyé brings to the table. The second is the careful arrangements provided by the singer, Bada Ken Okulolo, Tosin Aribisala, and Zem Audu. The arrangements display a clever sleight-of-hand that leads the listener to hasty conclusions of where the song is going, only to delight when it arrives elsewhere. An early example is the arrhythmic five bass notes anchoring Ray Noble’s “The Very Thought of You.” The experience is jarring until it reveals perfect sense. Douyé favors elastic tempos that slowly develop naturally. Another Ray Noble composition “Cherokee” is a study in rhythmic deception where she sings half-time to the music, which grows more percussively complex as the performance evolves. The song progressively builds from the talking drum introduction to an undulating eleven-piece little-big band exposition. The Kurt Weill/Ogden Nash “Speak Low” is introduced with its harmony melded with an angular percussion complex that leads the listener to hasty conclusions of where the song is going, only to delight when it arrives elsewhere.

The third innovation is experienced in the “guitar suite” made up of “Fly Me To The Moon” (Douyé’s homage to Frank Sinatra, part of her inspiration for this recording), “Afro Blue,” “It Don’t Mean A Thing,” “Green Dolphin Street,” and “I’m Confessin’ That I Love You,” Guest guitarist Lionel Loueke is featured on “Fly Me to the Moon” and “I’m Confessing That I Love You” where he underpins the songs’ percussion with a novel hand damping while contributing angular and compelling solos.

Not as widely mentioned in the press is guitarist Dokun Oke, whose contributions are equally percussive and harmonic and closely align with Najite Agindotan's dizzying myriad of percussive offerings. Densely layer African percussion and thoughtful, clever arrangements produce a productive environment for Douyé’s greatest asset -- her gracious yet muscular voice. Evenly balanced over volume and tone, it is an instrument that can color a piece warm or cool, loving and sensual.

It remains a valid question if one more jazz standards release can be justified when the market is clotted with them. Where Singer Cassandra Wilson dramatically interpreted the Songbook 30 years ago and Lyn Stanley has spent the 2000s as keeper of the flame of these sacred texts, can this durable, but well-worn repertoire reveal any more of her charms? Douyé proves so while eloquently restating the obvious -- this is where it all started and will always remain.

Douye is great!