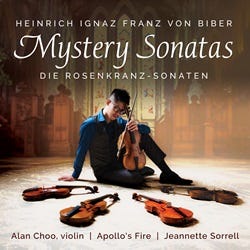

Alan Choo, Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell - Biber: Mystery Sonatas

Avie Records, 2023

Biber’s “Die Rosenkranzsonaten” (“The Rosary Sonatas”) is a work full of faith symbolism and not a little mystic appeal. One need not know a thing about the Rosary or anything else to be immersed in this sacred calm pool of praise and reflection, but a little knowledge adds much to the appreciation of Biber’s accomplishment.

The Rosary (“Garland of Roses”) refers to a set of prayers used in Roman Catholicism and to the physical entity composed of threaded beads used to count the component prayers contained in the set. Traditionally, the Rosary is arranged in five sets of ten Hail Marys (Ave Maria), called decades. Each decade is introduced by one Our Father (Pater Noster) which is followed by one Glory Be (Gloria Patri).

In the 16th century, Pope Pius V codified a standard 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, based on church tradition. These mysteries were divided into three sets: the Joyful Mysteries, the Sorrowful Mysteries, and the Glorious Mysteries. The three sets of mysteries are divided thusly (with Biber’s sonatas noted):

The Joyful Mysteries

The Annunciation (Sonata No. 1 in D Minor)

The Visitation (Sonata No. 2 in A Major)

The Birth of Jesus (Sonata No. 3 in B Minor)

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (Sonata No. 4 in D Minor)

The Finding of Jesus in the Temple (Sonata No. 5 in A Major)

The Sorrowful Mysteries

The Agony in the Garden (Sonata No. 6 in C Minor)

The Scourging at the Pillar (Sonata No. 7 in F Major)

The Crowning with Thorns (Sonata No. 8 in B flat Major)

The Carrying of the Cross (Sonata No. 9 in A Minor)

The Crucifixion and Death of our Lord (Sonata No. 10 in G Minor)

The Glorious Mysteries

The Resurrection (Sonata No. 11 in G Major)

The Ascension (Sonata No. 12 in C Major)

The Descent of the Holy Spirit (Sonata No. 13 in D Minor)

The Assumption of Mary (Sonata No. 14 in D Major)

The Coronation of the Virgin (Sonata No. 15 in C Major)

Each of Biber’s sonatas corresponds to one of the fifteen Mysteries followed by Sonata No. 16, Passacaglia in G Minor: The Guardian Angel for solo violin.

One of the lasting charms of Biber’s Mysteries is the fact that he did not define a basso continuo instrument to accompany the violin. This is not unusual as most baroque composers gave little instruction regarding the continuo, outside of what there was supposed to be. Performers could just use a keyboard instrument for the entire set as Andrew Manze and Richard Egarr did in their 2004 Harmonia Mundi release. Ensembles have been as accompaniment as was used in Reinhard Goebel and Musica Antiqua Köln’s 1991 Deutsche Grammophon Archiv reading. Or, a daring violinist could undertake the set, solus as Julia Wedman did in her 2011 Dorian Sono Luminus recording.

Apollo’s Fire artistic director, Jeanette Sorrell, contends that

“… the extraordinarily imaginative writing in Biber’s masterpiece calls for an imaginative and colorful approach to the accompaniment. The evocative possibilities of the continuo accompaniment, as partners in the storytelling, deserve to be explored with love and curiosity.”

Staying true to this conviction, Sorrell programmed differing combinations of baroque instruments: harpsichord, organ, cello, archlute, theorbo, baroque harp, viola da gamba, and lirone to accompany violinist and Apollo’s Fire assistant artistic director Alan Choo on his musical sojourn.

Choo is up to the challenge of the Mysteries, playing with the passion, fire, and brio called for to infuse these sacred pieces with the life they deserve. Creatively equipoise, Sorrell’s sensitive programming of accompaniment is inspired. The important opening (Annunciation) sonata has Choo’s rich woody tone nestled in the plush confines of a Sorrell-led quintet of harpsichord, cello, theorbo, lirone, and chamber organ. Choo’s violin emerges as if from sleep, the archangel Gabriel awakening the Blessed Virgin to tell her the future - a mini-Magnificat.

Other highlights include the Nativity sonata (No. 3) scored in a contemplative B minor that allows Choo to explore the peaceful gravity of the event while sharing a duet with triple harpist Anna O’Connell in the opening Sonata movement. The beautiful but brief adagio betrays a sadness foreshadowing future events. Here Choo is buoyed by René Schiffer’s viola da gamba and William Simms’s theorbo.

Sonata No. 10, The Crucifixion’s short Praeludium section opens with the grand mal expression of the violence and rage of the nailing to the cross. This gives way to the lengthy and plaintive Aria - Variatio where Choo and company use the G minor key to divine the slow grief and transfiguration of the event.

The Joyful and Sorrowful Mysteries make up the first of two discs with the Glorious Mysteries given a full disc of their own. The centerpiece is the three-part Resurrection Sonata, No. 11. The Sonata section features a rippling triple harp introduction that gives way to Choo’s exposition of identical figures played high and low, accented by the theorbo. The Surrexit Christus hodie section is soothed by Peter Bennett’s chamber organ enabling some of Choo’s most lyrical playing. The slim Adagio marks the close of the day, Choo easing double stops drawing the curtain on the day sacred to so many.

The closing Passacaglia is a crowning achievement in Baroque violin composition. Choo treats it gently with a necessary reverence that never smothers the piece, only enhancing its importance. The solo passage is not a formal part of the Mystery Sonatas but acts as a watchman reminding us in contemplation that we are never alone.

Choo provides excellent, even delightful notes on each sonata and Biber’s use of scordatura tuning to sharpen the pieces, revealing new light and darkness. Sorrell’s portion of the notes is informative and her argument for her choices for continuo instrumentation convincing.

Recordings for comparison

Manze, Andrew, Richard Egarr, Alison McGillivray. Biber: The Rosary Sonatas. Harmonia Mundi HMU907321/22, 2004. CD.

Goebel, Reinhard, Musica Antiqua Köln. Biber: The Rosary Sonatas. DG Archiv E4316562, 1991. CD.

Wedman, Julia. Biber: The Rosary Sonatas. Dorian Sono Luminus DSL-92127. 2011. CD.